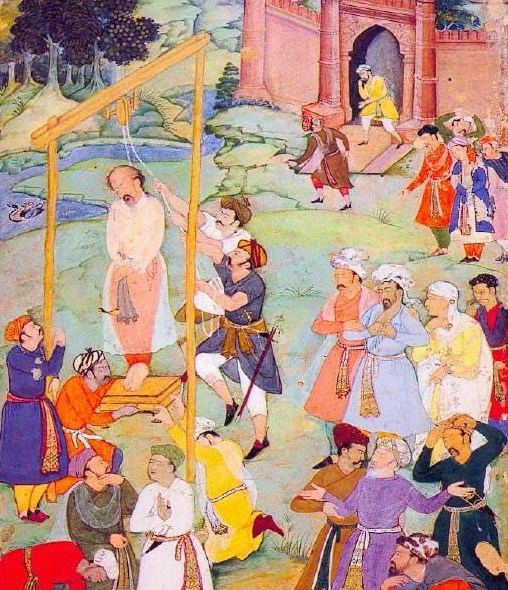

Late depiction of the execution of Hallaj at Baghdad, as rendered by a seventeenth century artist in Mughal India, namely Amir Najm al-Din Dihlawi.

|

The figure of Hallaj became a legendary appendage to Sufi hagiology. Dismissed and condemned by Islamic orthodoxy as a heretic, Hallaj was later resurrected in the pages of a multi-volume scholarly work by Louis Massignon. The attendant political situation at Baghdad, in the early tenth century, led to the downfall of the Abbasid empire.

CONTENTS KEY

1. Research of Louis Massignon

2. Early Life

4. The Basra Phase and Zanj War

7. Sorcery Myth and the Universalist Tendency

8. The shahid ani and the Sufi abdal

9. Problems of the Abbasid Empire

12. Aftermath

13. Reflections

1. Research of Louis Massignon

There is no figure in early Sufism who has been more debated and variously depicted than Abu'l Mughith Husayn ibn Mansur ibn Mahamma Baydawi, commonly known as al-Hallaj (c. 858-922). Islamic orthodoxy regarded him as a dire heretic; the Sufis assimilated his inspiration to varying degrees. In more recent times, the French Islamicist Louis Massignon (1883-1962) portrayed Hallaj as a martyr undergoing a "passion," a theme inviting associations of Christianity. Massignon was a leading Roman Catholic intellectual (Gude 1997; Waardenburg 2005). His sympathetic presentation broke new ground in Islamic studies, being remarkable for the degree of empathy demonstrated.

Louis Massignon, 1913 |

From the age of 25, Professor Massignon studied many documents relating to Hallaj. An Islamicist at the College de France, he produced an erudite book on the subject, originally published in French in 1922. This later developed into a four volume work gaining an English translation. (1) The Passion of Al-Hallaj has been frequently cited, and sometimes contested. The copious bibliography attests to the prodigious labour involved. One can use the data supplied by Massignon without accepting a number of his interpretations. (2)

Massignon became dubbed a "Catholic Muslim." While criticised by some Catholics for his affinity with Islam, he was opposed by some Muslims for giving attention to Sufism, the mystical sector of Islam strongly associated with Hallaj. (3)

A necessity to penetrate legend applies in the instance of Hallaj. Some conservative Muslim critics objected that Massignon exaggerated the importance of Hallaj in Islamic history. Massignon certainly filled a gap in the conventional history of the Abbasid era, providing a detailed outline of events in the life of his subject, while incorporating much information about religious and political trends in the Islamic world of the late Abbasid era. (4) The French scholar admitted ingredients of Greek philosophy in the influences upon Hallaj. However, he did not give much credit to pre-Islamic Iranian religion. Above all, Massignon emphasised the Islamic context, correcting some former European misconceptions. He revealed the extent to which hostile Muslim commentators had distorted the portrayal of Hallaj during the medieval period.

"Hallaj was probably of Iranian, not Arab stock, despite what people said to the contrary later." (5) He was born circa 858 near Bayda, a town in the Iranian province of Fars. This south-western area of Abbasid Iran was still strongly Zoroastrian in population and culture, though the process of conversion to Islam had commenced. The paternal grandfather of Hallaj was a Zoroastrian. His father Mansur, who became a Muslim, was apparently an artisan at the Islamised suburb developing outside Bayda. Hallaj may have been reared from the start in the Arabic language; however, some contemporary Iranian Sufis were not familiar with the new prestige tongue.

Though many of his family group appear to have become Muslims, a minority remained Zoroastrians. "His mother must have been an Arab: of the Harithiya." (6) That detail is not clear, however. The same scholar affirms that Hallaj "did not have maternal Arab parentage." (7) This is the reason given for his location in the mawali sector of Iranian converts to Islam, who are noted for their crafts prowess.

Hallaj was a Sunni Muslm. Nevertheless, he early had two Shi'i Muslim friends at Bayda. His father was a cotton carder (hallaj), a profession thought to be intermittently practised by the son, hence his name. Mansur subsequently moved to the textile centres of Ahwaz and Tustar in the adjoining Khuzistan province of West Iran, eventually settling his family at the Arab town of Wasit in southern Iraq. Young Hallaj lived in that Sunni bastion for several years, being educated in the emerging Hanbali tradition of Quranic exegesis. Some analysts allow that he only became fully Arabicised at this juncture; he may therefore have possessed a childhood knowledge of Persian. He later composed in Arabic.

At Wasit, Hallaj was taught Arabic grammar and the Quran by Hanbali traditionists (muhaddithun). However, at the age of sixteen he left this conservative milieu, setting off for Tustar, a town in Khuzistan where he became the pupil of Sahl al-Tustari (c.818-896). While Sahl gained the repute of a Quranic scholar, he was also a mystic, teaching in a different way to the exoteric traditionists of Wasit. From an early age Sahl had lived an ascetic existence, accustomed to fasting; he had travelled to Basra, Kufa, and Mecca in search of guidance. Sahl also stayed for about two years at Abbadan, the ascetic island retreat (on the Tigris) in Iraq, a site which seems to have been his major inspiration. Back at his native Tustar, he composed a commentary (tafsir) on the Quran that is associated with his contemplative discipline.

The Tafsir of Sahl does not depict God as an aloof creator, but as the ultimate destiny of man, in whose pervasive light man will be absorbed. The human being is depicted as deriving from God, as an infinitely small particle of light. Man has to penetrate his own essence, and in so doing, realize God as the "secret of the self" (sirr an-nafs). The human self (nafs) has both a positive and negative aspect. The positive and most essential aspect is comprised by the divine spark of light incarnate in the human being. The negative aspect is frequently mentioned in the Tafsir, relating to self-assertion, self-centredness, and other diverse egoistic tendencies that cause so many problems. Like Hakim al-Tirmidhi and other early Sufis, Sahl al-Tustari depicts human consciousness as the scene of a struggle between these two conflicting tendencies, amounting to a basic gnostic dualism. (8)

Circa 860, Sahl al-Tustari emerged from ascetic seclusion as a teacher with a circle of disciples. Becoming a controversial figure, he had to leave Tustar for Basra circa 877. He aroused the opposition of legalists by his claim to be hujjat-Allah (the "proof of God"), a theme associated with the awliya ("saints") who became celebrated in the formative lore of Sufism. Such unorthodox claims were viewed as a challenge to traditionist authority. However, Sahl was careful to avoid overt political conflicts, and did not side with opponents of the Abbasid Caliphs; he emphasised conformity with the Quran and sunna (tradition).

Sahl al-Tustari apparently expressed disapproval of miracle stories concerning him. The eleventh century Sufi annalist Qushayri reports that Sahl was believed by enthusiasts to walk on water without getting his feet wet. Sahl himself referred such admirers to the local mosque official who had rescued him from drowning. (9) A disposition to miracle stories became pronounced in the popular Sufism of later centuries. Sahl himself became a legendary Sufi.

At Basra, Sahl achieved profile as a mystical traditionist. There were some affinities here with the contemporary Baghdad "school" of Sufism, though also differences. Similarities include the stress on repentance (tawba), the conflict between the lower self (nafs) and the heart (qalb), and belief in a spiritual hierarchy of saints (awliya). The differences extend to his vegetarianism, plus "his peculiar 'light' cosmology centred on the idea of 'the light of Muhammad', and the conviction that he could access the 'inner meaning' of the Quran." (10)

Meanwhile, the young Hallaj studied under Sahl at Tustar for two years, leaving him for reasons unknown. His departure for Basra occurred at a fraught period of political unrest, when the Zanj revolt and related developments threatened Tustar, which had to be evacuated. Sahl himself was exiled to Basra soon afterwards, the harassing legalists being another problem. "Hallaj retained throughout his life the stamp of Sahl's practices and ideas," (11) including the ascetic discipline and struggle with the nafs. Both of these figures moved to Basra, a town in Southern Iraq, predominantly inhabited by Arabs. Basra was associated with the nearby island of Abbadan, site of the first Sufi monastery founded in 767 CE, visited by pilgrims like Sahl. The monastery was apparently destroyed in 874 during the Zanj revolt.

4. The Basra Phase and Zanj War

Iraq and Ahwaz, 869-883 CE. Courtesy Ro4444, Wikimedia Commons |

Basra, located in southern Iraq, was a garrison town during the Islamic conquest. The Arab army, composed of Bedouin tribesmen, established their base circa 638 CE on the site of a Zoroastrian settlement (Vaheshtabad Ardashir) which they destroyed. Basra saw the convergence of many Arab tribes, some of whom were traditional enemies, a situation conducive to uprisings. The population of early Basra was predominantly Arab; a minority Iranian element included captives and mawali (converts to Islam). The increasing commercial activity attracted Indians, Malays, and Africans.

From the eighth century CE, cosmopolitan Basra also became significant as a place of intellectual activity, including entities of Iranian blood. Grammarians, poets, historians, and others were in evidence. Arabic was the prestige tongue. The growth of the new Abbasid capital at Baghdad increased the demand for luxury goods. Basra accordingly derived prosperity as a commercial centre, some merchants even being involved in trade with China. See F. M. Donner, "Basra," Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

Hallaj did not profess Sufism (tasawwuf) until he moved to Basra. He there adopted the woollen robe (khirqa) that became identified with Sufis. This uniform was apparently acquired during an initiation by the Arab traditionist (muhaddith) Amr ibn Uthman al-Makki (d. 903/4). An early form of the much later Sufi initiation system was in favour at that period amongst Sufised traditionists.

This conversion was part of a complex situation in which, during 877, Hallaj married the daughter of Abu Yaqub Aqta al-Basri, a disciple of the famous Junayd of Baghdad (d.910). Al-Basri apparently came from a distinguished family of Iranian scribes associated with Ahwaz. This was the only marriage contracted by Hallaj, producing three sons and one daughter. One of those sons, Hamd, contributed an account describing a quarrel between Hallaj and another disciple of Junayd, namely Amr ibn Uthman al-Makki, who disapproved of the marriage. Hallaj is reported to have travelled north to Baghdad, to resolve this matter with Junayd himself. The latter apparently advised patience. Hallaj returned to the home of his father-in-law at Basra. (12)

The intellectual development of Hallaj has been differently explained, being rather more complex than the standard Sufi conversion and ascetic vocation. The hagiographies were reductionist; modern scholarship has revealed something of the detail and implications.

Basra was not an idyllic place at that period, the Zanj war afflicting the vicinity during the years 869-83. The Zanj were black slaves imported from East Africa; many of them laboured in Southern Iraq, as part of a reclamation project for rebuilding neglected canals and creating sugarcane plantations. Lands in the Tigris-Euphrates delta had become marshes, subject to flooding, and abandoned by migrating peasants. Black slaves had been toiling in Southern Iraq for two centuries and more.

To the east of Basra salt marshes were reclaimed by Caliphs, Arab governors, and rich tribal shaykhs, encouraged by a policy of land and tax concessions. Caliphs and governors in particular sought to generate private revenues apart from taxation. To work the new lands, they imported slaves from East Africa in large numbers, thus creating the only plantation-type economy in the Middle East. (13)

Depiction of Zanj rebels |

During this period, the Abbasid Caliphate experienced reverses at their new capital of Samarra, north of Baghdad. The removal to Samarra occurred, in 836 CE, because the oppressive Turkish troops were unpopular at Baghdad. During the 860s, rival military factions reduced the Caliphs to mere puppet figures after Turkish guards murdered al-Mutawakkil (rgd 847-61) at the instigation of his son. The orthodox Mutawakkil was a persecutor of Jews and Christians; however, he was not removed for that reason by ambitious schemers. The Caliphate eventually returned to Baghdad in 892, striving to assert Abbasid supremacy over diverse territories.

Meanwhile, a figurehead for revolt was the obscure Ali ibn Muhammad, alias the Sahib al-Zanj, who claimed to be the Alid saviour of the slaves. Probably of mixed origin, he was reared at Samarra, where he lived as a court poet familiar with slaves. In 863 he moved to Bahrain, claiming to be a descendant of Ali. In Arabia he mobilised Shi’ite followers against the Abbasid regime, but lost credibility with the Arab tribes after losing a battle.

Ali transferred to the marshlands near Basra, where abject black slaves were used by wealthy landowners. Tabari suggests that about 15,000 black (zanj) slaves were involved in digging out salt to reclaim the land for plantations; the salt layer was piled into giant mounds. The oppression was severe, the cruel overseers being indifferent to suffering. The Zanj slaves were forced to live on a meagre diet of little more than flour and dates. This form of slavery was very different to the domestic household slavery found elsewhere in Islamic countries.

The Zanj slaves were forced to dig ditches, drain marshland, clean salt flats by removing salt crust, and cultivate cotton and sugarcane plantations. They had to work in malaria-infested swamps, while living in dirty huts made of reeds and palm leaves. A high mortality rate was replenished by a constant supply of enslaved black victims from East Africa (McLeod 2016:117-18). The African slaves had a very low value in the Abbasid economic system, far less than white slaves.

When Ali’s initial attempt to gain support at Basra was squashed, he retreated to Baghdad. Returning later, he concentrated upon the Zanj slaves, whose mood was ripe for rebellion. In 869 he proclaimed the Zanj revolt. This versatile leader captured groups of slaves and their detested overseers, liberating the black slaves and giving them whips to dominate the overseers (who now became slaves). He trained the Zanj to fight. However, at first they were using sticks and farming tools as weapons, with only a few swords amongst them. The Zanj women threw bricks during battles (McLeod 2016:122).

Massignon described the Basra drama as the first example of urban social crisis in Islam. The luxury of the wealthy class was a source of exasperation to the poor; exotic jewellery, African ivory, and Gulf pearls were only a few of the status symbols in evidence. The Basra crisis “ended in a fight to the death between the privileged elite of the City that wanted everything for itself, and the starved proletariat of the plantations and sand-filled oases who pounced on the City” (quoted in Derek Ide, Against Ignoring Race, 2019; Popovic 1999:24-5).

The Zanj slaves found that they were denied any claim to freedom after conversion to Islam. Other grievances were nurtured by the “poor peasants” or Bedouin tribesmen, who joined the Zanj army created by Ali and his black slave assistants. Some commentators say that the majority of slaves were of Nubian or Ethiopian origin. They built the new town of al-Muktarah, constructed not far from Basra.

Major sources are the Islamic historians Tabari and Masudi, both of whom were biased against the Zanj. Tabari's History of the Prophets and Kings includes a detailed version of the Zanj war. The Zanj army fought on territory familiar to them, a location of marshes intersected with canals. They lured their Abbasid enemy into ambushes, and beheaded prisoners. They captured weapons, horses, and boats from the Abbasid forces. Boats were crucial in this amphibious war of the marshes. Catapults were used by both armies. The Abbasid soldiers catapulted severed rebel heads over defending walls in an attempt to demoralise the Zanj guerilla action. Atrocities were committed on both sides of this conflict.

At the outset of rebellion, the Zanj were forced back from an attack on Basra. A local army of pro-Abbasid volunteers went in pursuit, only to encounter a deadly ambush, leading to “the almost complete annihilation of the Basran army” (Adam Ali, The Zanj Revolt: A Slave War, 2019). The Abbasid leaders then despatched elite Turkish troops to quell the revolt. The invaders were unable to negotiate the marshland, being driven out of the swamps to Basra. Afterwards the Zanj rebels defeated another army and blockaded Basra in 870. The rebel leaders sent money and supplies to desert tribes for the purpose of enlisting Bedouin fighters. Arab horsemen now supported the Zanj infantry. After a year, the Zanj leaders exacted a grim revenge on the population they blamed for their afflictions. Probably 10,000-20,000 men were massacred at Basra, while women and children were taken as slaves to al-Mukhtara.

Thereafter the Zanj defeated every army sent against them. The prolonged slave revolt gained extensive territory in Iraq. The Zanj army raided towns like Wasit, burned plantations, and destroyed slave markets. The underdogs fought ferociously, tenaciously surviving. They generally looted and then abandoned the towns they captured. Military strength was afforded by black soldiers who defected from Abbasid armies to join the Zanj (McLeod 2016:121). By 879, the Zanj controlled most of Southern Iraq and Ahwaz. Indeed, they even advanced to within fifty miles of Baghdad.

A reverse occurred when the amplified Abbasid army slowly pushed the rebels back into the marshland, eventually containing the Zanj at al-Mukhtara. "The final battles featured chemical warfare (naphtha) that ignited fires in the enemy's wooden structures, bridges, and ships" (Fields 1987:xiv). However, the strong resistance caused the Abbasid commander al-Muwaffaq to offer amnesty to any rebel wishing to defect, meaning they could join the Abbasid army. The revolt ended in 883 when the Sahib al-Zanj was captured and beheaded. Ali’s remaining supporters were granted amnesty to prevent any further problem. One consequence was an end of the plantation scheme in Iraq.

Vast numbers are reported to have died in the Zanj war (the statistics in Arabic are considered to be inflated by modern historians). Yet “it would not be an exaggeration to put the estimate of the death toll in the tens or even hundreds of thousands” (Adam Ali, article last linked). This conflict devastated agricultural lands of Southern Iraq, resulting in a major decrease of revenue for the royal treasury. Some regions were afflicted with food shortages and famines. The adverse situation greatly weakened Caliphal rule. The Abbasid Empire started to shrink, eventually to a dramatic extent the following century.

At the end of the Zanj war, the Caliph was still iiving in Samarra, the military centre. "The imperial governmental machine was split between Samarra and Baghdad. Both, however, evinced an atmosphere redolent of endless intrigues, plots, and secessions" (Fields 1987:xiv-xv). The Abbasid regime could be merciless. When Yahya of Bahrain, a Zanj rebel leader, was captured and sent to Samarra, the Caliph al-Mutamid (rgd 870-92) watched while the victim was flogged 200 times, suffered the amputation of his arms and legs, and had his throat cut.

Hallaj is associated with the Zanj phenomenon; he would certainly have heard much about the struggle with Abbasid armies. We do not know how he viewed the ferocious Zanj war. His in-laws have been identified with the Shi'ite Karnabai family, who ideologically approved of the Zanj revolt. That family were mawali (convert) notables of Basra. (14) "We believe that through his brother-in-law, Hallaj lived in the milieu of the Zanj pretender [Ali ibn Mhd], a Zaydi Shi'ite milieu permeated with gnostic propaganda" (MA:11). The intricacies of doctrinal formulation in this sector are prodigious. Massignon emphasised the dissident attitude of Hallaj to the milieu he partly supported. "His grammatical and theological (jafr) lexicon will remain marked throughout his life by this reaction against extremist Shi'ite tribal members" (ibid).

The viewpoint of the young Hallaj was radical "from the time of his youth when he demonstrated against the Caliphal authorities on behalf of the Zanj salt field labourers condemned in southern Iraq to subhuman living conditions and slave labour, a position he repeated on behalf of starving Bedouins who stormed Basra and Baghdad desperate for food." (15)

The father-in-law of Hallaj, Abu Yaqub Aqta, is described as a khatib or secretary, a role implying a scholarly background rare among Sufis of this period. The brother-in-law of Hallaj was Muhammad ibn Said Karnabai of Basra, apparently one of those locals who supported the Zanj revolt. Hallaj seems to have been in some affinity with his brother-in-law. Sympathisers with the Zanj revolt were in danger of being considered extremist Shi'ites by other Muslims. Hallaj evidently felt that the negro slaves (and destitute Bedouins) were the victims of a doctrinal rigidity and ruling class elitism, an Abbasid convenience ignoring human rights and reducing spiritual perspectives.

Massignon may have been correct to infer that Amr al-Makki was jealous of Aqta, having wanted Hallaj to be his own son-in-law. Makki was an Arab who organised pilgrim caravans to Mecca; he gained repute as a Sufi. There developed a custom amongst Sufi shaikhs of marrying their daughters to promising disciples. Makki advised Hallaj to accept the Sufi robe. The young Iranian was twenty years old when he visited Junayd, and may have become a disciple of the latter. However, some analysts consider that the "disciple of Junayd" image was exaggerated in later Sufi annals; Hallaj may only have encountered Junayd on one occasion.

During this troublous period, the Sufis of Baghdad were verbally attacked by the preacher Ghulam Khalil (d.888). Their leader, Abu'l Qasim al-Junayd, is said to have adopted the defensive image of a jurist, maintaining a conventional decorum. Born in Baghdad, his ancestors came from the Iranian town of Nihawand. Junayd's father was a glass-merchant (qawariri). He himself became known as a silk merchant (khazzaz); he was also skilled in the study of Islamic law.

It is reported that al-Junayd restricted the number of people with whom he spoke on sufism to no more than twenty.... When he wrote to a friend, he would word his letter very cautiously.... The sufis held that ultimate religious truths contained an element of mystery and that none should reveal this element of mystery to the uninitiated....Towards the end of Junayd's life, the School of Baghdad suffered much. The sufis were accused of being atheists, infidels and believers in re-incarnation. Every member of the school, including al-Junayd, was publicly accused of heresy.... Ghulam al-Khalil raised the case against the Sufis before the Khalif [Caliph] al-Muwaffaq. Junayd described himself as being simply a jurist by profession and thus escaped the court. (16)

There developed a legend of friction between Junayd and Hallaj, giving the impression that Junayd admired his junior as a mystic but condemned him from the viewpoint of a canonist. Junayd is said to have criticised Hallaj for being too "intoxicated." The senior is alleged to have indicated that Hallaj was unstable in dissociating himself from the tuition of Makki. Junayd himself subsequently dissociated from Makki when the latter accepted an officious position of qadi (judge) at Jeddah, a role evoking the strong disapproval of Junayd. Although such figures are now classified under the conglomerate label of Sufism, some strong differences of outlook existed amongst them.

The preacher Ghulam Khalil seems to have been especially averse to the theme of hulul, denoting a divine indwelling in the soul, interpreted as a threat to conventional doctrine by jurists and theologians. Some of the Iraqi Sufis were probably partial to that theme, which Hallaj appears to have employed extensively. His version should be distinguished from some later confusions. By the eleventh century, the doctrine of hulul had gained the strong disapproval of "orthodox Sufis." Hujwiri refers to "two condemned sects" of Sufism, namely the Hululiyya and the Hallajiyya. (17)

The Zanj war ended in 883, the rebels being defeated and assimilated to the Abbasid army. The Caliphate regained control over Basra. Hallaj departed from the scene, undertaking a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he stayed in retreat for a year, leading an ascetic existence. Sahl al-Tustari was apparently keeping a low profile at Basra; he did not figure any further in the career of Hallaj, who at some point became ostracised by Makki. The standpoint of Hallaj at this time is not sufficiently clear. His unorthodox outlook was also rejected by his father-in-law Abu Yaqub Aqta, who probably followed the general tactic of conciliation with Sunni legalism. Hallaj relinquished the formal Sufi robe (which he apparently wore at Basra during the Zanj war). This gesture emphasised his tangent to the Baghdad school, and probably also the Basran tradition (nevertheless, he retained Sufi garb as one of his varied costumes in subsequent years).

Hallaj returned to his wife (Umm al-Husayn) at Basra, where he began to speak forthrightly about his beliefs and experiences. These disclosures were apparently the cause of rift with Aqta and Makki. He moved on with his wife to Tustar, possibly because of verbal harassment from Makki, who sent accusing letters from Basra. "Amr Makki must have been doing a lucrative 'business' on the Meccan hajj," (18) meaning the pilgrim caravans he organised.

A political complexion to this rift has been deduced, in that Makki was averse to Shi'ite connections of Aqta's Karnabai family. The position of Aqta must have been complicated by his imprisonment with the related Karnabai family of notables at Basra, who were associated with the Zanj revolt. Aqta conceivably adopted a conservative position in the interests of safety.

The split with Makki is reported to have derived from a difference of view concerning private revelation. Makki evidently did not hold the same view about mystical inner states. Hallaj angered Makki by viewing "interior words" as coming from "the same God who dictated the Quran." In the sources, "Makki denounces Hallaj, not without treachery, as having become a heretic, a false prophet of a new Quran." (19) Makki subsequently sent letters of complaint about Hallaj to eminent persons in Khuzistan, a campaign which caused Hallaj to discard the Sufi robe and to wear instead the coat (qaba) associated with the military, thereafter "frequenting the company of worldly society (abna' al-dunya)." (20) The transition to a different milieu of influences is memorable.

At Tustar, Hallaj is reported to have preached (in Arabic) to local audiences, who have been deduced as Iranians conversant only with a smattering of Arabic. Massignon deduced that Hallaj could not speak the Persian dialects, so he needed intermediaries who translated his words. The popular overtones of this vocation can be misleading, because the idiom of Hallaj was not "orthodox Sufism" but something rather different. He was not wearing Sufi garb, and adopted a vocabulary that could be assimilated by the local Shi'ite population. According to Massignon, his projection had affinities with dialectic of both the Mutazilite theologians and the Shi'ite literati of south-west Iran, a dialectic associated with the formation of philosophy (falsafa). His teaching only survives in fragments, sometimes glossed by the medieval commentators.

The basic trend discernible is that Hallaj moved out of the "ascetic Sufi" milieu into an intensive contact with the "men of the world," meaning the Iranian literati, who were often bureaucrats and landed gentry, with strong interests in Greek philosophy, medicine, alchemy, and astrology. This elevated social stratum has been assessed in terms of the continuation, under Islamic auspices, of the scribes (dibheran) of the Sassanian era. For a lengthy period, these men preserved Pahlavi traditions (associated with Zoroastrianism) alongside their newly acquired use of Arabic. Many of them appear to have been Shi'ites. Nestorian Christians and Jews were also to be found in the ranks of these literati, often with strong interests in Greek philosophy. Islamisation frequently amounted to a veneer amongst this intellectual sector of the population in Iran and Iraq. Even quasi-Buddhist influences have been discerned by the late tenth century, though after the time of Hallaj.

This milieu was an important seedbed for the Muslim version of Greek philosophy, known as falsafa, developing in Baghdad and elsewhere. In relation to this trend, "support for speculative thought and experimental research was cultivated, particularly in science, philosophy, alchemy, medicine, and literary anthologising and criticism; traditionalist Muslim piety and asceticism became interiorised and weakened in such centers." (21)

Mutazili rationalism gained different inflections. The contingent sometimes known as "right wing Mutazilis" were not in agreement with Hallaj, opposing his deference to the hierarchy of saints associated with Sufism. Mutazili theologians repudiated saintship and the powers believed to be achieved by this category. They are thought to have been instrumental at an early date in interpreting popular rumours of "miracles" (credited to Hallaj) as proof of his charlatanism. Hostile sources claim that he created fake phenomena in a special room at Basra contrived for this purpose (though one interpretation is that another entity, with the name of Hallaj, was here being described). Both Mutazilis and Sunni legalists accused him of "sorcery." The gossip may have originated via Hermetic associations in the idiosyncratic "Sabaean" milieu of Basra. Hallaj is reported to have acquired a knowledge of medicine and alchemy; Massignon suggested that the Iranian mystic probably read the Arabic version of the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus.

In his thirtieth year, Hallaj was briefly arrested by Sunni agents and publicly flagellated at Diri, between Sus and Wasit. The Sunni authorities mistook him for a political agitator, possibly an emissary of the Qarmati community, radical Shi'ites who were strongly opposed to the Abbasid government. The Sunni inquisitors believed that he was pleading the cause of an Alid mahdi (saviour). However, the only "mahdi" Hallaj is known to have designated was Jesus, concerning whom he made apocalyptic references as part of his obscure gnostic philosophy. His selection of Jesus as a figurehead has inevitably aroused scholarly speculation; this feature may have been a consequence of his sympathetic contact with Nestorian Christians, or simply a result of his focus in a liberal form of "Sufi asceticism." He was not here employing conventional Shi'ite imamology; indeed, many Imami (Twelver) Shi'is grew resistant to him.

The individualism of Hallaj makes him a difficult subject for commentary. His references to the imam (spiritual leader) were of an esoteric type; Massignon emphasised the gulf between Hallaj and both the Imami Shi'is and the ghulat ("extremist") Shi'is who were very active at that era. His version of the controversial doctrine of hulul (indwelling) can be interpreted as meaning that he himself was a human reflection of the "resurrection" of Jesus - not in any sense of a divine incarnation but in terms of a "God-realisation" attainable by gnostics who adhered to the disciplined path of inner purification.

The popular Sufi legend of Hallaj became that of the "intoxicated" mystic unable to restrain his expression of mystical secrets. Ironically, Hallaj gives indication of having concealed his innermost teachings, with an elaborate sense of caution. His opponents accused him of infidelity in assuming the religious terminology of whichever doctrinal grouping he was communicating with at the time. His underlying strategy was apparently that of negotiating all barriers of religious dogma.

This strategy has not always been viewed in adequate perspective. Louis Massignon, for instance, was quick enough to discern Christian affinities of the subject, while curtailing implications applying elsewhere. A mystic like Hallaj might conceivably have addressed the Qarmati rebels (22) on equal terms, in a universalist manner. Any assumption that he was an Ismaili/Qarmati missionary is no more convincing than to imagine he was a convert to Christianity or Judaism. He remained a Sunni Muslim, though an unorthodox specimen.

Massignon theorised that Hallaj was influenced by Abu Ishaq Ibrahim ibn Sayyar al-Nazzam (c. 782-836), a Mutazili opponent of the Manichaean religion; this attribution was employed to suggest that Hallaj opposed the evolutionism of the controversial and contemporary philosopher Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Rhazes), who favoured the theme of transmigration (tanasukh). This theme was heresy to Islam, and also to Massignon. It is far less certain that Hallaj was so inflexible. (23)

Massignon was generalising against the Qarmati and Druze beliefs in reincarnation; however, there were different versions of tanasukh. While resisting any implication of a strong philosophical link between his mystical hero and Razi, Massignon wanted to believe that Hallaj fitted the Christian concept of the Passion of Christ (without being an Incarnation), a belief which he explicitly tenders in such reflections as: "Hallaj appears before the observer as a strangely living image of the real Christ as we know him." (24)

The commentary of Professor Massignon found proof of the "real Christ" in the hagiographical report that Hallaj extinguished a sacred fire of the Mazdeans (Zoroastrians), "a mission reserved for the Messiah." (25) The report of Ibn Hajj says that Hallaj miraculously relit the flame in the Zoroastrian fire temple at Tustar, when a visiting group of Sufi shaikhs had been gifted the contents of the temple coffer. (26) Such stories prove nothing about the real nature of events.

The commentator must be cautious in accepting the theory of Nazzam's influence on the subject. Nazzam was a zealous member of Mutazili circles at Baghdad, where he denounced the heresy (zandaqa) of Manichaeans. (27) Nazzam died at Baghdad many years before Hallaj was born. Razi's version of Greek philosophy was radically different to the dogmatic views of right wing Mutazili theologians (mutakallimun). Hallaj himself appears to have been in basic opposition to Mutazili attitudes, whatever conciliatory gestures he may have expressed on occasion.

Hallaj may have been in search of disciples; however, his procedures were not typical of missionary enterprises, including Ismaili variants. There seems no doubt that Hallaj often did preach, though not in the customary manner of Quranic zealots or Sufi ascetics. He was not a Ghulam Khalil, meaning the vengeful preacher at Basra who had opposed Nuri and others. Furthermore, the historically verifiable links between Hallaj and Hanbali traditionists and tradesmen of Baghdad prove that he was not bent upon opposing Sunni Islam. Nevertheless, he did evidently feel that aristocratic and bureacratic habits were unduly oppressive for the populace.

A specialist commentary refers to the opposition of Hallaj to "political extremism and tyranny of any colouration." He also distanced himself from "quietistic Sufism," meaning the approach associated with the Baghdad school of "detachment and withdrawal in prayer from any engagement in political activity." (28) His form of activism was so very unusual that diligence is needed in confronting this phenomenon.

Hallaj evidently found himself in a predominantly Shi'ite milieu, one which is rarely understood outside scholarly circles. That milieu did not resemble the much later Shi'ite environment of Safavid and Qajar Iran, when clerical hierocracy and complex doctrines had emerged. The Shi'ite milieu of Hallaj "had been deeply imbued with Hellenistic and neo-gnostic cultural attitudes and thought throughout the century of his birth." His emerging eclecticism was influenced by "a philosophical vocabulary and a dialectic mode." To be sure, he was a defender of the Quran, though some Sunni enemies accused him of "being a Shi'ite or even a Christian in disguise." (29)

After the public flagellation, he left the scene and travelled in distant lands, moving through Khurasan as far as the Oxus River, to the comparative freedom of the Saffarid and Samanid milieux. Hallaj was reputedly on good terms with the rulers of Balkh and other Central Asian cities. He seems to have gained a following amongst the Khalaj Turks, who had become Islamised but not rigidly orthodox. It was possibly during this lengthy sojourn, in the eastern territories of Islam, that a colony of his followers was established at Talaqan, in the vicinity of Balkh. Massignon referred to a dual Hanafite and Shi'ite support attaching to that colony; the ghulat (Shi'ite "extremist") undercurrent was indicated by posthumous events, when the colony reportedly declared Hallaj to be the mahdi, in defiance of official proscription at Baghdad.

7. Sorcery Myth and the Universalist Tendency

In 893, Hallaj returned to Fars and Khuzistan, rejoining his wife and writing his first books. Nearly all of his writings have been lost, save for some poetry and his distinctive Kitab al-Tawasin, described as a miscellany of fragments. (30) That work is too brief and aphoristic to give any complete idea of his teachings, but suffices to indicate the complex gnostic character of his thought. In that text, he "frequently employs line diagrams and cabbalistic symbols, in what seems to be a determined struggle to convey profound mystical experiences which he could not express in words." (31)

According to the reconstruction of Massignon, in presenting his arguments, Hallaj fully accepted the data of the Aristotelian organon.

He uses the ten categories and the four causes, and the last five chapters of his Tawasin are based on syllogisms. But he went even further: he called himself namusi (from the Greek nomos, law), which is reminiscent of Socrates; the God whom he preaches, al-Haqq, the Truth, bears a name common to several religious movements, one that had been already emphasised by his teacher Tustari, but which was taken here absolutely, and clarified by the Greek, [Arabic] mu'ill, 'first cause'.... His definition in this instance combines with that of Proclus, while on the geometric question it returns to that of Plato. (32)

In 894, Hallaj made a second pilgrimage to Mecca. At this time he was accused of charlatanism by the Imami Shi'ite leader Abu Sahl Nawbakhti (d.924) and the Mutazilite theologian Abu Ali al-Jubbai (d.916). The relevance of such accusations is in dispute. Popular imagination may have credited miracles to him. The situation tended to attract sectarian animosity, and to be diagnosed in terms of sorcery by theological reckoning. Nawbakhti has the more insidious repute of being an opponent of Hallaj over a lengthy period.

The heretic is said to have arrived in Mecca with 400 disciples, which could easily be an exaggeration. The Meccan authorities regarded him benignly, though some Sufis were hostile. The accusation was contrived that Hallaj had made a magical pact with the jinn (demons). This amounts to pious calumny.

Abu Yaqub Nahrajuri circulated the rumour that Hallaj was served by the jinn, alleging that a cake and a cup were miraculously transported to Mecca from distant Zabid by the demons. Nahrajuri was a former admirer of Hallaj, strongly influenced by his continuing allegiance to Makki and Junayd, who represented conservative versions of Sufism (Makki is said to have likewise accused Hallaj of sorcery). The interpretation of Nahrajuri argued for the superiority of "revealed texts and tradition" over "ecstasies" associated with Hallaj. (33) The net result of hostile stories about heretics is a strong degree of reservation about the accusations.

Bizarre anecdotes about Hallaj seeking magic and displaying miracles can be sceptically viewed. The Indian "rope trick" is one feature of this lore. According to the interpretation of Massignon: "Hallaj never claimed to have the gift of miracles; those that he showed in public were only juggler's tricks, innocent sleights of hand used for gathering the crowd that he wanted 'to evangelise.' " (34)

However, there is the contradictory statement: "In his later preaching, Hallaj presents his miracles as mujizat, or immediate acts of God and signs of a divinely ordained public mission." (35) There are references in the anecdotal literature to such matters as the cures for illness he achieved. A very late anecdote says that one of his enemies slapped him, and when asked by Hallaj to repeat the aggression, the aggressor's hand promptly withered away. (36) Such stories could obviously be manipulated in the oral circulation.

The issue of miracles remains a point of vexation in different interpretations of Hallaj. According to Massignon, the miracles of Hallaj "are not the later embellishments of legend... they appear, though interpreted in different ways, in all the early texts." (37) Those texts tend to be compositions made after the death of Hallaj. Sixty years after his death, one commentator remarked about the Hallajiya (followers of Hallaj): "They attributed to him absurd things," (38) analogies with Zoroastrian and Christian hagiology here being adduced.

The rationale of Massignon included an observation that the conservative Sufi traditionists believed there could be no public miracles, the last having been the revelation of the Quran; there could only be private miracles, and these were forbidden in terms of public exposure. The conservative Sufis instead preferred "the dualism of a purely external literal law and a purely individual mystic esoterism." (39) Under such constraints of attitude, Hallaj may have been keen to prove that alternatives were possible, whatever precise inflection he himself imparted to the Arabic terminology surrounding "miracles."

Baghdad was originally a circular city built by the Abbasid Caliph Mansur (rgd 754-775 CE). This city was intended to accommodate an expanding bureaucracy and cosmopolitan population, though religious orthodoxy was promoted. The original city was subsequently eclipsed by a large settlement on the opposite side of the Tigris River, which became the main city in the late ninth century. The divided bureaucracy failed to establish due solutions for the common people, a tragic situation witnessed by Hallaj. |

Returning to Tustar, Hallaj soon left this Iranian town permanently. He emigrated to Baghdad in 896, a few years after the Caliphate returned to that city from the temporary base at Samarra. The old circular "City of Peace" was outmoded by a growing population on the opposite bank of the Tigris. The royal building projects in the new settlement included palaces featuring much opulence.

Hallaj was joined by a large group of "Ahwazi notables," meaning followers belonging to the Iranian scribal class of Khuzistan. They settled in the Tustari textile quarter of Baghdad. Massignon inferred that these supporters were now bazzazin, meaning cloth and brocade merchants. There would appear to have been a strong Iranian crafts element attached to this grouping, who are thought to have established at Baghdad a branch of the weaving factory in Tustar known as Dar al-Tiraz, the major centre for luxury textiles, which gained the prestige of weaving the annual covering for the Ka'aba at Mecca. This Hallajian community would appear to have been financially self-supporting.

In common with many Sufis, Hallaj is thought to have resorted to the manual trade of his father, that of a cotton carder. This artisan background is significant in relation to certain social developments. The role of cotton carder was a humble vocation, separated by four removes from the mercantile status of bazzaz. Fabric manufacture passed from the carder to the cotton sorter, the spinner, the weaver, and the tailor, all proletarian trades whose eventual output passed to the cloth merchant, whose market (suq) served as a bonded warehouse. Hallaj would have known how easily the worker could be exploited and depressed. He had gained an unusual Arabic religious education in Wasit that most Iranian cotton-carders would not have possessed. However, he did not follow any role of a privileged legist, being instead a nonconformist mystic.

The town of Ahwaz (in Khuzistan) was noted for the export of cotton fabrics. Cotton plantations had developed in that region of Iran, with a resultant increase of weaving shops in the towns. The trade in cotton created a working class proletariat who had been sympathetic to the Zanj revolt. There was also a more widespread development in towns such as Isfahan, Tustar, Wasit, Mosul, and Cairo; a strong division emerged between workers and merchants, the latter benefiting as middlemen to the consumers. The increasing corruption and luxury lifestyle of the Abbasid court at Baghdad played a strong hand in urban business. The privileged classes exploited the situation, until eventually the consumer complaints grew acute. At the end of the life of Hallaj, riots occurred in Mosul and Baghdad (followed by others in Mecca), led by bread-sellers, fruit-sellers, and other categories who opposed the merchants and warehouse system. (40)

Hallaj preached at Baghdad in a basically proletarian milieu, appearing in marketplaces. Mosque entrances and private houses also feature in the anecdotal reports. A difficulty exists in being definitive about the nature of all these events. The report of Jundub Wasiti informs that he accompanied a wealthy Zoroastrian to the Baghdad abode of Hallaj with a purse of 1,000 dinars intended for the mystic. Hallaj was reciting the Quran, and refused the gift. However, because Wasiti entreated him to accept, Hallaj relented. When the Zoroastrian guest departed, Hallaj took Wasiti to the mosque of al-Mansur, where he distributed the gift amongst poor people, "without keeping anything for himself." (41)

Hallaj at first stayed for a year in Baghdad, apparently not yet preaching. He was reputedly in contact with amenable "independent" Sufis, notably Nuri (d.907) and Shibli (d.945). Abu'l Husayn al-Nuri, who had displayed heretical tendencies, was formerly exiled to Raqqa; in 877 he was interrogated on charges of heresy (zandaqa) brought against him and others by the preacher Ghulam Khalil. Nuri had been acquitted, departing for Raqqa (in Syria) for many years. He returned to Baghdad in the early 890s, remaining aloof from the circle of Junayd, though becoming well known at the court of the Caliph al-Mutadid (rgd 892-902). (42)

Gaining the assistance of a Caliphal envoy, Hallaj embarked for India, afterwards moving north to Khurasan. There he pressed on to reach Turkestan (Balasaghun) and probably also Ma Sin, meaning Qocho (near Turfan, in "Chinese Turkestan"). Qocho was the capital of the Uighur Turks, who were Manichaeans. Massignon interpreted the apocalyptic Hallajian references to mean that the objective of Hallaj was to convert the infidel Turks, though "if he preached, he did so through Soghdian interpreters and Nestorian or Manichaean scribes." (43) Very little is known of this phase.

Manuscripts of his treatises are reported to have been transcribed in the Manichaean style, i.e., using the expensive materials of gold ink on Chinese paper adorned with brocade and silk. At the end of his life, these manuscripts were found by Abbasid officials in the homes of his disciples at Baghdad, and deemed proof of zandaqa (heresy). The general context might merely prove the author's universalist tendencies. His son Hamd reported that Turkish followers (perhaps even ex-Manichaeans) wrote enthusiastic letters to Hallaj after his return to Baghdad; they called him al-Muqit, "the nourisher." Hamd admits that he only half understood the content of his father's public preaching at Baghdad in the final years. (44) The conclusion is possible that the private teaching was even more complex, and furthermore, that the conversion of Manichaeans was rather more subtle than orthodox associations of preaching might suggest.

Professor Herbert Mason has emphasised the universalist dimension to Hallaj, in terms that extend far beyond the conservative tendencies of Sufi traditionalists and others:

He was accused by his enemies of dissimulation and opportunism by associating with neo-Hellenists, philosophers, aesthetes, pseudo-mystics, magicians, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, Manichaeans, Hindus, Buddhists, the rich and the poor, indiscriminately on his travels throughout the Near East, Iran, India, and possibly even China; and at home with adepts of radical Shi'ism while claiming the heritage and identity of a strict [Sunni] traditionalist. (45)

An earlier version of this universalist tendency is evident among the followers of Mani, the third century Gnostic leader whose approach was amenable (with ideological criticisms) to Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Buddhism. Their missionary activity occurred over a wide area, the early phase being suppressed by the Mazdean priesthood of Iran, (46) strongly associated (like Mani) with the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon, located in Iraq, not far to the south of Islamic Baghdad (and in the same zone as Babylon).

Ruins of Sassanian palace, Ctesiphon |

Adjacent to the Hellenistic city of Seleucia, Ctesiphon was "one of the most important cities of the rich agricultural province of Babylonia, which, with its network of waterways and fertile soils, supported a dense population." The ethnic and religious complexity of this earlier phase is indicated by the observation: "Although situated in the heartland of the Sasanian empire, Ctesiphon and the surrounding area were inhabited mainly by Arameans, Syrians, and Arabs, who spoke Aramaic and were predominantly Christian or Jewish." Quotations from Jens Kroger, "Ctesiphon," Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

Ctesiphon became known to the early Muslim conquerors as Al-Mada'in, at that time still a sprawling urban complex. The Arab army resettled at Kufa after discovering that the Mada'in environment was malarial. Mada'in was left with a small garrison, the diminishing population tending to be pro-Shi'ite and anti-Kharijite. In 687/8 the marauding band known as Kharijite Azariqa sacked the old city and massacred the Muslim population, an indication of the acute violence emerging in the early schismatic conflicts of Islam. By the eighth century, the surviving Shi'ites of Mada'in were ideological "extremists" (ghulat), some of them believing in reincarnation.

A stern Umayyad policy of demilitarising the violent Arab tribesmen was furthered by Al-Hajjaj, the governor of Iraq (692-715), in whose day Syrian troops were favoured. Al-Nadim records that a Manichaean secretary of Hajjaj built an oratory at Mada'in for Zad Hormuzd, an obscure entity who claimed to be the Manichaean leader. Mada'in declined after the founding of Baghdad by the Abbasid Caliphs, certain of whom are known to have demolished Sassanian buildings of the older city for purposes of using the stone. By the ninth century, Mada'in was mainly an agricultural centre. See Michael Morony, "Mada'en," Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

In Iraq, the Abbasid authorities applied the word zandaqa (of Iranian origin) primarily to Manichaeans, a word conveying the accusation of dire heresy. This stigma could also be applied to mawali newly converted to Islam, whose Quranic affiliation was often a veneer for habits of vegetarian asceticism, secret initiation, and attendant concepts associated with the Manichaean outlook. In particular, that convert milieu had preserved a teaching known to Muslims as hulul al-Ruh, recently translated as "infusion of the Spirit in the heart, transmitted from initiate to initiate." (47) That doctrine was known in variants to "extremist Shi'ites" of Iraq, also denigrated as zanadiqa.

According to Massignon, the distinctive preaching of Hallaj was aimed at "all Muslims, from the most traditional Sunnites to the most extremist Shi'ites." This liberal inclusivist "had even devised for himself an Arabic metaphysical vocabulary, which was sometimes borrowed from profane sciences developed by independent minds outside Islam." (48) Unlike other Sufis, Hallaj knew the language of Greek logic; he made recourse to some medical terms, and reputedly visited the celebrated hospital of Jundishapur, located between Tustar and Sus in Khuzistan. That hospital was strongly associated with transmission of the Hellenistic medical tradition. Massignon suggested that, via Nestorian medics, Hallaj could have made contact with some falasifa (philosophers) of the school of Al-Kindi, Muslims like Sarakshi and Quwayri or Nestorians like the logician Matta Qunnai.

Jundishapur dated back to Sassanian times; that town (or city) was created by the monarch Shapur I (rgd 242-72), being the scene of Mani's imprisonment and death, according to extant tradition. The population were predominantly Nestorian Christians, surviving the fourth century persecution; the town was still prosperous in the early Islamic period (though later abandoned). The sources indicate that the local Nestorians maintained a substantial degree of (Galenic) medical learning, subsequently disseminated to Muslims by the learned Bakht-yashu family of Nestorians at the Abbasid court. See A. Shahpur Shahbazi and L. Richter-Bernburg, "Gondesapur," Encyclopaedia Iranica online. By 900 CE, the science of medicine was being enthusiastically studied by Muslims throughout the Islamic world, notably al-Razi, the philosopher (and medic) who composed an extensive medical encyclopaedia (al-Hawi), including extracts from Greek and Indian (i.e., Hindu) writers.

Massignon asserted that Hallaj encountered the distinctive Iranian philosopher Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (c.864-c.930), who lived at Rayy. This contact is considered conjectural (or erroneous) by some recent scholars. Massignon duly mentions Baghdad as the scene of Razi founding a large hospital, being supported in this venture by the Queen mother Shaghab, who esteemed Hallaj. A recent interpretation affirms that confusions occurred because there were two men on record with the name of Hallaj, the namesake being a Qarmati whose reputation as a magician and conjuror was mistakenly conflated by posterity with the Sufi Hallaj. (49)

Razi was a talented medic and chemist. "His alchemy, with its Persian nomenclature and updated stock room, comes closer to chemistry than anything found in the Hellenistic sources." (50) Razi, a Platonist believer in reincarnation, was troubled by the suffering of animals, whom he regarded as part of the transmigratory cycle of souls. His freethinking tangent tended to be sceptical of prophetic revelation. Islamic posterity was frequently condemnatory in his direction, including the Ismaili instance of Nasir-i Khusrau, the prominent missionary (dai) of the eleventh century. Razi was "held in almost universal contempt as a schismatic and an infidel." (51)

Though the purported contact between Hallaj and Razi is uncertain, it is of interest to compare their roles. Hallaj was likewise posthumously denigrated as a heretic by so many conservative persuasions within Islam. According to the version of Massignon:

Every man of good will is suited to attain purification of the soul, through a progressive training of his reason, according to AB Razi, and through an asceticism of heart, according to Hallaj. And though the Razian notion of progress based on experimental science fi'l tariq ila-Haqq, 'on the way toward the Truth,' agrees to some extent with the Hallajian idea of mystical ascent, Hallaj nevertheless condemned... the work in which the noted doctor challenged the miracles of the Prophets. (52)

8. The shahid ani and the Sufi abdal

Returning to Baghdad after five years, Hallaj soon made a third pilgrimage to Mecca in 902, staying there in retreat for two years. Massignon elaborates his role in terms of the shahid ani ("present witness"), a theme implying "traversing the continuous chain of apotropaic saints, the abdal (and not the discontinuous cyclic reappearances of Shi'ite Imams)." (53) Hallaj is here representative of the Sufi abdal, meaning an elite group within the spiritual hierarchy of awliya (saints) elaborated by later Sufi authors like Hujwiri.

The abdal belief is found in variations, apparently first introduced by minority Shi'ite "extremists" (ghulat). Indeed, the Arabic presentation of abdal and awliya "was probably of non-Muslim origin, deriving from a common, ancient Near Eastern source." The tenth century Sufi version affirmed that a fixed number of these elect were divinely chosen, and "by their presence, preserve universal equilibrium, especially during periods between prophets" (quotations from J. Chabbi, "Abdal," Encyclopaedia Iranica online).

Hallaj was also credited by Massignon with the incentive for a distinctive martyrdom. Certainly, he thereafter placed himself in a metropolitan role that struck to the core of sociopolitical tensions within Islam. In 905, Hallaj returned to Baghdad, where he began to preach directly to the crowd for the first time, "no longer inside a ribat or from a mosque, but in the open street, in the markets; and, in order to be spontaneous, these speeches offer, in contrast to those of truly popular sermonisers, some stylistic and technical refinements of expression that even an Arab urban public could hardly grasp without direct commentary." (54)

In the Tustari quarter of Baghdad, he built an unorthodox enclosure containing a miniature Ka'ba, designed for private celebration of the hajj (Meccan pilgrimage). Hallaj explained that he was transferring the privilege of the hajj to his own emigre community, the Tustariyun; he was here implying that the official hajj was Arab-controlled, and represented an expensive and dangerous undertaking for many mawali (non-Arab converts to Islam), not all of whom were able to make the laborious journey to Mecca. A subsequent (and unconvincing) accusation made against him by officialdom was that Hallaj sought to destroy the Ka'ba in Mecca, making reference to circumambulating "the Ka'ba of one's heart."

At a Baghdad mosque, Hallaj reputedly said to his Sufi friend Shibli, "I am the Truth (Ana'l-Haqq)." This is regarded by some scholars as unverifiable legend. Perhaps more important was his emphasis upon the priority of saintship (wilaya), buttressing the related views expressed by Al-Tirmidhi (55) more than anyone else known at this period. Hallaj insisted upon the intercession of saints and their capacity for supernatural achievements. Mutazili theologians and others resented any priority given to Sufi saints. However, the most formidable opposition came from treasury officials and wazirs (vizirs) pursuing suspect fiscal policies. Hallaj evidently wanted moral reform, entailing the redistribution of exorbitant taxes and corrupt appropriations of public earnings. He nevertheless evaded a political commitment against the government, even though some of his sympathisers were keen to take this approach.

His preaching at Baghdad lasted for several years. Hallaj was effectively in competition with popular Hanbali pietist preachers and Shi'ite equivalents. According to Massignon, his spontaneous delivery would involve "a sort of 'ecstasy of jubilation' unfolding itself before the crowd." (56) Hallaj tends to emerge as a distinctive ecstatic, observing a lifestyle of strict renunciation, while contacting diverse social strata, including the salons of Baghdad, frequented by the wealthy classes and featuring diverse entertainments. This activity demonstrated a significant aspect of his abstruse mystical philosophy, combining renunciate achievement with an active polarity in the mundane world.

Hallaj claimed to have acquired a mystical union with "the One who is at the heart of ecstasy." (57) In the interpretation of Massignon, the "negative asceticism" associated with Junayd is but a preparation, while the "intoxication" associated with Abu Yazid al-Bistami is not the ultimate experience. The essential personality or "self" of the mystic is not destroyed in the ultimate action. "In the essence of union (ayn al-jam), all the acts of the saint remain coordinated, voluntary, and deliberate, by his intelligence, but they are entirely sanctified and divinised." (58) These complexities do not admit of immediate verification, but are perhaps indication of possibilities seldom understood, even in circles where knowledge is assumed.

At nights Hallaj would withdraw in contemplation to a secluded corner of the Quraysh cemetery, near the tomb of the celebrated traditionist Ibn Hanbal. He would exhort some disciples to observe ten day retreats of fasting and prayer. Yet at the same time, he himself achieved an "in the world" orientation via his connection with the working class and also the "upper class" of the salons and private houses. It was possible to project controversies in both the street and the salon, more especially via poetry. This appears to have been one aspect of his underlying intention. Hallaj had "put into verse a sarcastic eulogy of the esoteric discipline professed by Sufis" (59) a gesture evidently deriving from his rift with the formal Sufism of Amr Makki. He clearly felt that the Sufi discipline was prone to myopic application and dogmatic distortion.

Hallaj apparently had a distinctive habit at Baghdad of invoking his own death, as distinct from any political revolution. Whatever the mystical complexities of his public preaching, this activity is said to have strengthened a desire for social reform in accordance with religious ideals. Hallaj was apparently regarded by some followers as the leader (shahid ani) of the saints known as abdal. Those followers included eminent men in different regions with whom he was in correspondence; he is said to have written works on political theory and the duties of wazirs, subsequently lost. "There was at that time, even among the ulama [religious scholars], a general desire to purify the administrative machinery: they demanded a government that was sincerely Muslim; a vizirate that rendered justice, especially in fiscal matters." (60)

The basic gist of Massignon's theory, about the preaching of Hallaj, is that the radical was exhorting his audiences to the disciplined life of Sufis, generally occurring in hermitages and other private milieux. The primary audience of Hallaj in the marketplaces were apparently Arabs, identified with the Karkh and Bab Basra localities. More specifically, these were ex-Bedouins, with a background of hunger and suffering, displaced tribesmen fleeing from famine and the Qarmati revolution. They amounted to an ex-nomad proletariat, having migrated from the regions of Basra and Kufa, and even distant Bahrain, under pressure from dire social circumstances. Some of them were perhaps ex-Qarmatis, disillusioned by the problems occurring. Generations ago, Bedouin Arabs had been the front line warriors in the Islamic invasion; now the fighters were Turks, Berbers, and other nationalities assimilated by the Abbasid empire.

An early opponent at Baghdad was Ibn Dawud al-Isfahani (868-909), leader of the Zahiri school of law, who was in some affinity with right wing Mutazilite theology. Ibn Dawud was party to dogmatic concepts, despite his repute for being conversant with the Hellenistic philosophy of Al-Kindi (d.c.866), who became known as the first Arab philosopher. Mutazilis were not philosophers but theologians, despite some familiarity with Hellenistic concepts; the right wing Mutazilis were in opposition to Sufis, their lifestyle of wealth and stipend contrasting with ascetic withdrawal of the latter contingent (the left wing"Sufi" Mutazilis, exercising an ascetic orientation, are relatively unplumbed). The attack of Ibn Dawud apparently started in the reign of Al-Mutadid (892-902), at a time when popular preachers and story-tellers (qussas) were the target of a restraining edict.

Ibn Dawud objected strongly to the theme of mystical love taught by Hallaj. To love God (Allah) was considered an impossibility, as "the majority of theologians taught that God could not be loved." (61) The proscribing vehemence of Ibn Dawud was offset by a guarded defence expressed by the Shafi'ite jurist Ibn Surayj, who indicated that his role was not qualified to pronounce upon such matters.

9. Problems of the Abbasid Empire

The city of Baghdad was founded in 762 by the Caliph al-Mansur, the second Abbasid monarch. That urban centre has been described as the largest city ever built by that time in the Middle East. During the ninth century, Baghdad comprised an extent of about 25 square miles, even bigger than Constantinople. The population was intensive at somewhere between 300,000 and 500,000 people. Only China had anything that could rival this phenomenon.

The southern district of proletarian al-Karkh initially accommodated the numerous construction workers from Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Egypt. None of the original structures survive, though Iranian influence has been deduced in such features as the circular ramparts of the Caliphal quarters (the Round City). To the north was the military district known as al-Harbiya, where many soldiers were (initially) of Iranian origin. However, the strongest influx of settlers was represented by the Arabs and local (Aramaic-speaking) Nabateans from Kufa. "Despite the strong Persian element in the population, Arabic was the vernacular language of the city" (H. Kennedy, "Baghdad i. The Iranian Connection," Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

There was a boom in international trade, assisted by the cosmopolitan population (which included clandestine pagans). Many Nestorian Christians migrated to the capital from villages throughout Iraq, duly gaining representation in the bureaucracy. Amongst a learned minority, scholarship flourished, associated with ancient centres like Harran, Jundishapur, and Alexandria. Christians, Jews, and Muslims all figured in the learned minority. Iranian scholars became a strong presence, eventually infiltrating the clergy (ulama).

Some historians describe the Abbasid dynasty in terms of jettisoning the earlier Arab supremacy of the Umayyad period, dispensing with Arab military privileges. The tenth century Islamic historian Masudi reported that the second Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur (rgd 754-75) was the first to employ his mawali freedmen in official positions, favouring them above Arabs; later Caliphs followed his example, and in this manner, Arab Muslims lost the leading positions.

Later European historians tended to portray the Abbasid Caliphate as losing a democratic orientation, the monarchical pomp and ceremony increasing to despotic proportions, being reminiscent of Sassanian tendencies. This rationale seemed supported by a trend of prominent Iranian families gaining salient official positions. However, recent analysis favours a "a more graduated picture" of the theocratic monarchy, one not restricted to the Persian/Arab dichotomy, instead encompassing a recognition of concepts "common to nearly all the ancient Near East, from Egypt to Persia, with the exception of the Arabian peninsula."

Moreover, the origins of Shi'ism, and the messianic lore of the Mahdi, have been traced to the Arabs of Kufa and southern Iraq. The expanding Abbasid empire created a complex bureaucracy; the role of Iranian mawali (converts to Islam) was encouraged in that context within Iraq and Iran. The role of wazir (head minister) was formerly conceived in terms of direct borrowings from Sassanian bureaucracy, yet "it now appears that the office has its roots in early Arabic practice" (quotes from C. E. Bosworth, "Abbasid Caliphate," Encyclopaedia Iranica online).

In many respects, the ninth century Abbasid cultural milieu of Baghdad was a remarkable innovation, outstripping the confines of any single ethnic component, and giving some leeway to a new cosmopolitan identity. However, events did not work out successfully; in the tenth century a contraction process occurred, accompanied by a disintegration of the ruling elite. Eventually, the "ancient" learning dwindled, being eclipsed by a traditionalism of the Islamic religious establishment that was hostile to "Greek" and related elements. So what went wrong in the train of events?

The problems developing in the Abbasid empire were prodigious. The bureaucracy gained a reputation for corruption. "Abbasid bureaucracy came to be dominated by cliques and factions, formed among the functionaries, whose main interest was to exploit bureaucratic office for private gain." (62) The prominent ministerial office of wazir was frequently attended by some very doubtful habits. During the ninth century, "a wazir and his faction came to power by intrigues and by bribing the Caliph and other influential courtiers." (63) The office of wazir became notorious for "various frauds, such as padded payrolls, false bookkeeping, illegal speculations, and taking bribes." (64)

The central government, attempting to compensate for the financial losses that ensued, granted land concessions to soldiers and officials who would then collect taxes from the peasants. The resultant process assisted the formation of large landed estates which gradually absorbed small landlords and free peasants. Under pressure, peasants would sign over their lands, supposedly under protection.

Tax-farming was another ineffective counter-measure to corruption, one in which "the government sold the right to collect revenues to tax-farmers." This new breed of social parasite "profited by collecting taxes in excess of what they had to pay the state." (65) The problem amounted to a substitute form of administration, requiring a strict inspection by the government, who in practice effectively lost control of the revenues and the countryside. Tax farmers instead gained control of local administration and the local police.

The military situation declined, to the extent that provinces became independent of the empire. Turkish slaves were formed into regiments, being loyal to their officers rather than to the Caliph. In this way, Turkish guard officers could usurp provincial governorships and become independent of the central government, as occurred in Egypt with the advent of the Tulunid dynasty. The early Abbasid empire had relied upon the military support of Iranian subjects, whereas the later empire attempted to dominate the people with foreign troops (varying from Turks to Berbers), who were accordingly resented. The new administrative city of Samarra was built to the north of Baghdad during the 830s; the troublesome slave regiments were thus separated from the urban populace. The problematic Samarra phase lasted for several decades, leading to rivalries among the regiments that killed the presiding officers and led to banditry.

When the Caliphate returned to Baghdad in 892, a lavish building project achieved new palaces thought to have been influenced by Sassanian traditions of royal splendour. "From this period we have tales of elaborate court ceremonial, of vast and opulent palaces and golden birds singing in silver trees which were alien to early Islamic styles of monarchy" (H. Kennedy, "Baghdad i. The Iranian Connection," article linked above).

Meanwhile, the Abbasid rulers lost both Egypt and Iran to the new wave of martial rebellion. In Sijistan (south-east Iran), a mass revolt of frontier soldiers (ghuzat) occurred. The ghazi was the "holy warrior" of Islam, apparently condoned by the Quran for jihad (holy war). The Saffarid dynasty led that uprising, thereby gaining control of Khurasan and West Iran, even invading Iraq. The Saffarids were eventually defeated by the Samanid dynasty of Transoxania, who were prepared to cooperate with the Abbasid central government. The distant Samanids achieved a high degree of culture, representing the same landowning and administrative system which created the Abbasid empire. That system had been ousted in many areas by ghazi rule and innovations.

In 905, the Abbasid Caliphate defeated the rival Tulunid dynasty in Egypt and Syria (created by a private slave army). This proved a hollow victory. The bureaucracy was in a process of irreversible decline. The new military victories were quite insufficient to reorganise the Abbasid empire, a prospect that was desperately needed. "These victories were but a lull in a downward course which became headlong between 905 and 945." (66)

The decline of central government also meant demise of the provincial landowning and scribal class which had originally supported the Abbasid dynasty. In particular, the introduction of tax-farming, which required significant investments, benefited the interests of merchants and bankers who had become rich through international trade. Bankers gained additional political importance as a consequence. The new mercantile entrepreneurs began to replace the scribal class. Despite the extensive wealth passing through private hands, "in the course of the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the economy of Iraq was ruined." (67)

The ecology factor was typically ignored by bureaucratic and mercantile greed. The almost continual warfare caused extensive damage to the irrigation system attending the Tigris River. The creation of tax-farming and allied facilities of the rich monopolists "removed all incentives for maintaining rural productivity." (68) Fiscal exploitation led to ruin of the rural environment. Large districts suffered a depopulation. For a thousand years, Iraq became one of the poorest countries in the Middle East, despite the former degree of marked agricultural prosperity dating back many centuries.

With the decline of Abbasid power in the early tenth century, prosperous urban Basra regressed into a rural problem, continually at the mercy of local Arab tribes who were in the habit of plundering the town. By the mid-twelfth century, Basra was largely in ruins, the population much reduced. In 1495 the original site of Basra was abandoned because of a scarcity of fresh water; modern Basra is over 20 kilometres to the east (see F. M. Donner, "Basra," Encyclopaedia Iranica online).

In Abbasid Iraq, peasants abandoned the land because of Bedouin raids and excessive taxation. Large numbers of Bedouin Arabs (as distinct from urban Arabs) had settled in Iraq during the seventh century, with the first onrush of Islam. "In the course of the ninth century, there was a general regression of sedentary life under nomadic pressure." (69) However, this trend was perhaps less obvious than the metropolitan problem in Baghdad, created by corrupt politicians and ambitious landowners. The capital was effectively sundered from the provinces, which had gained an autonomous existence.

Critical observers must have been well aware of the growing tendency of the Abbasid empire to administrative and military collapse, despite the show of opulence in the Baghdad palaces.

Hallaj became closely involved (as a victim) in the situation attending the Caliph al-Muqtadir (rgd 908-932), whose violent period of fraught rulership was "marked by the rise and fall of thirteen vizirs [wazirs], some of whom were put to death." (70) Muqtadir had predominantly Greek blood. He became Caliph at the age of thirteen, too young to have been properly educated, while gaining many concubines. (71)

Orthodox Sunnis hatched a revolutionary plot at Baghdad that failed in 908. A group of Hanbali protesters tried unsuccessfully to implement reforms by installing a new Caliph, namely Ibn al-Mutazz, who contested the claims of his cousin Muqtadir. His reign lasted only one day; he was deposed and killed. The reformers lacked the financial support of Jewish bankers at the Baghdad court who were affiliates of the influential Shi'ite party. Massignon emphasises the gulf between the Sunni and Shia factions, clearly favouring the former, with whom he closely aligns Hallaj. The Shi'ite wazir (head minister) Ibn al-Furat (d.924) placed Hallaj under surveillance.

A year or so later, another Sunni reformist plot miscarried; Ibn al-Furat was warned in advance, acting on behalf of the young Caliph al-Muqtadir. Hallaj was considered a suspect influence upon the agitators, with whom he was in evident sympathy; the wazir ordered him to be arrested. However, Hallaj escaped from the volatile scene with his Karnabai brother-in-law. Police investigations were spurred by a major opponent, a Sunni tax-farmer named Hamid, or more fully Abu Muhammad Hamid ibn al-Abbas (d.924). This man, a landowner at Wasit, gained a role as one of the wealthy bankers at the Abbasid palace. Hamid is thought to have been influential in arranging the imprisonment of four disciples of Hallaj, though he may not have been solely responsible. Hallaj prudently retreated from Baghdad.

Tax-farmer Hamid does not emerge as an inspiring entity. Though he built a mosque in Wasit, Hamid gained a reputation for habitual drunkenness, "surrounded by hundreds of more or less armed slaves whom he called by the names of those who annoyed him in the [Caliphal] Court, his mouth full of obscenities which he considered witty." (72) Starting life as a low class water bearer and a vendor of pomegranites, Hamid later acquired riches via tax farms at Wasit, Basra, and in Fars. He is said to have achieved popularity by investing in alms that he lent to peasants, a procedure which was not the most admirable form of charity. Hamid's hatred of Hallaj stemmed from the criticism which the mystic and his associates "pronounced in loud and clear voices against a policy of unlimited fiscal exactions that were forcing the people into hunger, poverty, and rebellion." (73)